“And from this point on we’re in the alternate universe…”

“What?” I said. I literally said this to the television and demanded Kelly to repeat what he said. I’d watched Donnie Darko a couple of times prior to the commentary and his pronouncement caught me completely off-guard, making me question not only my understanding of his movie, but his understanding of his movie. Like most viewers, I considered the titular Donnie’s journey throughout the film to be a Lynchian dreamscape while his awake body quivered with fear over nuclear destruction, just as we all did in the ‘80s. When I viewed the “Director’s Cut”, I saw where Kelly labored to leave additional clues to time travel and alternate time lines, but I still felt, in the end, that I never would have come to those conclusions without him telling me. His commentary definitely changed my view of the film. Where before I thought it was enjoyable, trippy and intelligent, I was now thinking of it as a muddled, metaphysical mess.

So it came as no surprise to me when his sophomore film, the $17 million dollar-plus Southland Tales, with its stunt cast and visual tics, I viewed it as a plainly, laid-right-out-there-in-front-of-god-and-everybody, muddled, semi-metaphysical mess, albeit with some ham-handed satire. I enjoyed it, in much the same way I love fever dreams like Forbidden Zone and Dr. Caligari, but my final thought was that every scene was terrific, but none of them were actually in the same movie.

The film’s sprawling narrative takes us from a nuclear blast in Abilene, Texas, in 2005, to the “present” of 2008, where America is in the middle of a tight electorial race (the shudder-inducing Clinton/Lieberman vs. Eliot/Frost), is under the constant watch of Orwelian surveillance via the company USIDent (overseen by Bobby Frost’s wife, Nana Mae Frost (Miranda Richardson), is on the threshold of a new Tesla-esque machine that will turn the ocean into a perpetual motion machine of renewable energy, and an extreme Democratic Left-turned-terrorists, weilding guns and poetry and going under the umbrella of “Neo-Marxists”.

But that’s all background. The meat of the story involves an action movie star named Boxer Santaros (Dwayne Johnson) (married to Madeline Frost, daughter of Republican VP nominate Sen. Bobby Frost), who has been missing but was found with amnesia by porn-star-turned-talk-show-host Krysta Now (Sarah Michelle Gellar, who’s line about “I like to get fucked and I like to get fucked hard. But violence has no place in porn. That’s why I don’t do anal.” Surely caused some fanboy heads to explode.) The two of them wrote a screenplay called The Power, in which both will star, that tells about the last three days of the world, as prophesized by a newborn baby that has not produced a bowel movement in almost a week. To research his part, Krysta arranges for Boxer to ride-along with Officer Roland Taverner (an appropriately bewildered Seann William Scott).

Parallel to this, a Neo-Marxist group run by Cindy Pinziki (Nora Dunn) and Zora Carmichaels (Cheri Oteri) have hatched a plot to rig the election using “donated” severed thumbs, whose prints can be reused in multiple districts. Cindy (as “Deep Throat 2”) is also in possession of an incriminating sex tape starring Boxer and Krysta that could only spell scandall to the Frost campaign if released. In exchange for this tape she demands one million dollars and a vote of “Yes” on “Prop 69”, which will limit the powers of USIDent.

The third part of their plot seems to have been Zora’s brainchild. She forces the amnesiac Ronald Taverner to kidnap his twin policeman brother to pose as him and manipulate Boxer’s ride-along. The plan is to catch “Roland”, a “racist cop”, gunning down activist performance artists Dion Element and Dream (Amy Poehler), using blanks and squibs, of course. Once Boxer catches this assassination on tape, it can be used as further leverage against the campaign and Frost advisor Vaughn Smallhouse (John Laroquette).

Thirdly, there is Baron von Westphalen (Wallace Shawn), grandson of Karl Marx’s wife Jenny Von Westphalen, who is the genius behind “Fluid Karma”, the gigantic machine that harnesses the oceans waves to produce a continent-wide energy field to reduce America’s dependence on foreign oil—from which we’ve been embargoed anyway due to four Middle East Wars (Iraq, Iran, Syria and Afghanistan). But the Baron, far from a philanthropist, wants to use Fluid Karma for world domination.

Finally there’s the narrator, Pilot Abilene (Justin Timberlake), a disfigured war vet, omnicient from his perch in an anti-aircraft turret, who has ties to the major players, deals a drug version of “Fluid Karma” from his arcade on the Santa Monica pier, and warns us from the beginning, “This is the way the world ends: not with a whimper, but a bang.”

This reworking of the T.S. Eliot poem, “The Hollow Men”, is reiterated several times throughout the film. As are lyrics from Jane’s Addiction’s “Three Days”, The Killer’s “All the Things I’ve Done” (which is used as an extended music video-dream sequence starring Pilot Abilene and a group of nurses who are meant to look like Marilyn Monroe, but bear the platinum locks of Jean Harlow). The question is, are these lines meant to represent the weight of the narrative, or are they misdirects, giving over the propecy to dialogue like, “I am a pimp, and pimps don’t commit suicide.”?

I’m going to make a grand, sweeping statement that anyone will find Southland Tales impenetrable on first viewing, and may very well conclude at the nebulous anti-climax that it isn’t worth a second. That was certainly my attitude as the credits rolled. But something nagged at me. And continued to nag at me for a couple of years. Was there more to this pseudo-satirical jab at celebrity worship, government over-reach, fascism, Marxism, action film parody and theoretical physics than just all of the ingredients fed into a salad shooter and sprayed all over the viewer? Or is this another Donnie Darko, that will only make complete sense to its creator?

As I’ve found, on subsequent viewings, that the answer is probably a combination of the two.

When Kelly debuted a rough near-3 hour cut of Southland Tales at the 2006 Cannes Film Festival, it was met with jeers, boos and walk-outs. Notoriously, Roger Ebert wrote that it was as big a disaster as his most-hated The Brown Bunny. But Sony found promise in it and agreed to bankroll $1M worth of visual effects for completion if Kelly agreed to lose at least 20 minutes of running time.

“Part of me feels like I got away with murder,” Mr. Kelly, 32, said in a recent interview in Manhattan. “It’s a film some people might consider an inaccessible B movie, and it’s been slaughtered at the biggest film festival in the world. They could have been like, ‘You want more money now?’” (NY Times, by Dennis Lim, 10/28/2007)

Returning to the editing room, Kelly removed the requested twenty minutes, excising an entire subplot involving Jeaneane Garafalo as a military general working in collusion with Simon Theory (the gratefully-underused Kevin Smith), the only two upper brass who know the identity of the charred corpse found in Boxer’s SUV following his disappearance. Also reworked was the structure, moving a gruesomely funny scene involving the Baron and a Japanese business rival and the terms of a contract for Fluid Karma, from the first act to the second. Placing this scene later in the film manages to keep the Baron out of the “villain” role until much later. In the theatrical version, Wallace Shawn is simply a creepier version of The Princess Bride’s Vizini up until the “contract negotiation”. Further overtly villainous lines are also removed, but this also vagues up his connection to the Neo-Marxists, the identity of the burned corpse, and what role he expected Boxer to play in his scheme. While the Garafalo/Smith interactions didn’t add much to the plot (and only one scene with Smith had to be reworked to make it appear that he’s instead working under Nana Mae), but its removal makes a quick shot of Garafalo during the end celebrations a head-scratcher, but by this point, you should be through scalp and down to skull.

The real irony of the reworking is that the Cannes Cut is actually much more straight-forward of a narrative, inasmuch as Southland Tales can be considered straightforward. One thing that’s much more clear is how often Boxer slips into his character of Jericho Cane (an explicit dig/homage to Arnold Schwarzenegger’s character in End of Days) and the world of his screenplay when his psyche can’t handle the reality around him. Dwayne Johnson’s performance as Boxer among the highlights of the movie—when he’s stressed, he tents his fingers and twiddles them together, and to combat that he will “take a moment” and slip into the macho Jericho and, fortunately or not, the world of The Power. In the theatrical cut, this isn’t immediately clear and only alienates the viewer from the ostensible hero.

Kelly seems to have directed all of the actors to deliver lines as either stilted or overly-sinister. Then again, with so many hidden agendas, maybe it’s possible that every character suffers from some sort of identity crisis, even if they haven’t traveled back in time 69 minutes to meet their future selves.

The film’s primary problem lies in the fact that it does not stand alone as a film in its current state. It requires patience and multiple viewings, but, as I stated above, if one is feels completely disconnected from the characters by quirk and misdirected satire, those multiple viewings will not occur.

Then there’s the argument that Southland Tales was never meant to stand alone. Prio to the film’s release, Kelly wrote three prequel graphic novels which apparently give further clues to the story’s intricate mysteries: Abilene and “his best friend” (as he says in the last line of the movie) Roland Taverner were subjected to experiments in Iraq that resulted in a panicked Roland lobbing a grenade in Abilene’s direction, causing his disfigurement and PTSD. It’s also implied that Abilene and Taverner—and anyone who takes Fluid Karma injections—become telepathic. The comics also explain Boxer’s numerous tattoos and how he received them under Krysta Now’s guidance (including the portrait of Christ on his back that bleeds through his shirt during a critical point in the climax), and even why that dumb Killer’s song is relevant.

I came upon all of this knowledge after the fact, and in point of argument, rather resented it. I am aware, now, of the “immersive” marketing studios do now, leading fans to hidden videos and website scavenger hunts, but that still feels a bit like a cheat to me, especially if critical information is being withheld by this strategy. If the movie can’t stand as its own entity, then it isn’t really a movie, it’s something else. In this case, Southland Tales is a story told in six chapters, broken across three graphic novels and the three “chapters” presented in the film.

To call Kelly’s vision for the movie “ambitious” is akin to referring to the ocean as “damp”. Inspired by the events of 9/11, Kelly had a lot on his mind and did his damnedest to cram it all in: political culture, instant celebrity culture, the evils of the Patriot Act, the idea of perpetual war, PTSD, conspiracy and the near-magical realm of quantum mechanical coincidence.

It’s no wonder that any first viewing feels like a high-pressure mental delousing. As Kelly said in an interview for About.com: “You know, there’s always that risk [that the audience won’t get it]. But I think we’ve made it as accessible overload. It’s going to be overload. It’s one of those movies that’s going to melt your brain. It’s definitely going to melt your brain when you watch it, but I think it’s now going to melt your brain in a way where you’re understanding it just enough to keep going with it. And the important thing also is you’re laughing.” (Exclusive Interview with Southland Tales Writer/Director Richard Kelly By Rebecca Murray, About.com Guide)

When Southland Tales was finally released, it was met with largely negative reviews. Because, no surprise, nobody knew what the hell to make of it. Over the years, it’s started to garner a cult following and has shown up on at least one “Most Under-rated Movie” list that I’m aware of. And that’s because the film, for all of its goofy obtusity, is worth multiple viewings. Like a character in a Dan Brown novel, on the second or third time through you start to see the connections, albeit slowly. You begin to see how pieces fit together—particularly if you pay close attention to the multiple computer-voice readouts of news reports that are ubiquitous in the soundtrack background. And if you don’t mind pausing every few seconds to read the scrolling info on Abilene’s laptop screen, other clues can be found and other connections can be inferred.

Between the Cannes cut and the theatrical, I found a very rich, dense and thought-provoking satire. Had I not heard of the Cannes cut and managed to run it down, to be honest I might never have revisited the film. But at least as far as Southland Tales goes, it’s not the “makes sense in my head” movie that Kelly thinks he made. Rather it’s a mystery puzzle box with clues scattered throughout the frames and running time. If you want to make sense of it, the movie demands your participation. Otherwise, you’re just stuck in a room with a bunch of folks with violent tourettes trying to explain the Book of Revelations.[This article barely scratches the surface. Until I can further analyze this movie under controlled conditions, please check out this piece from Salon.com)

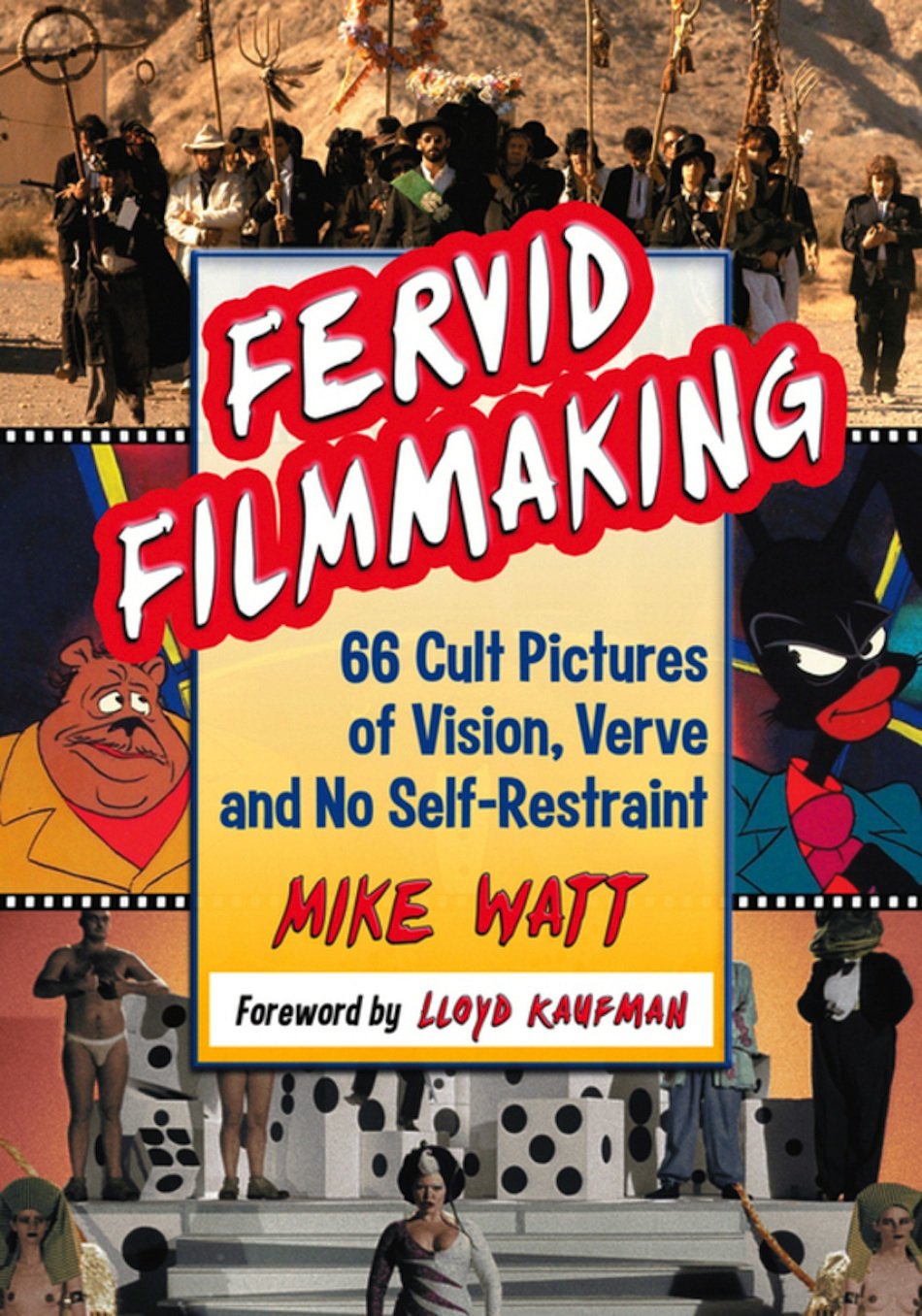

And don't forget to pick up your copy of