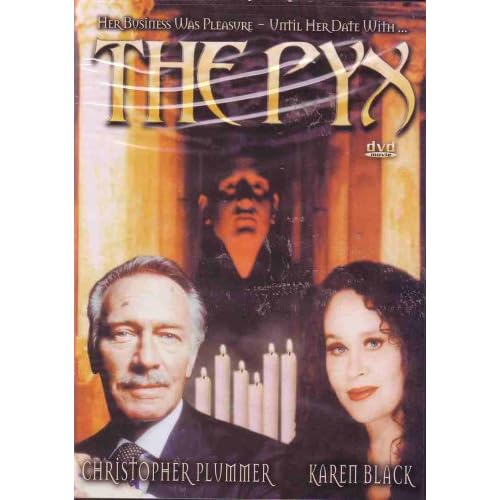

Canadian Det. Sgt. Jim Henderson (Christopher

Plummer) is called to the scene of a death that could have been suicide or

murder, and he’s leaning towards the latter. The body of a prostitute was found

on the ground outside a tenement building, in one hand a necklace with an

upside-down crucifix, in the other, a small round metal container on a chain.

Henderson quickly learns that the woman’s name was Elizabeth Lucy (Karen Black),

that she was a high-priced call girl working exclusively for a Montreal madam

and that she had a relatively severe heroin addiction. Following his leads,

Henderson’s suspects start turning up dead as well, murdered in perfunctory, if

gruesome, fashion.

Parallel to Henderson’s investigation, we witness

the last days of Elizabeth Lucy’s life. After an appointment with a regular

John, she helps a younger and similarly-addicted hooker escape the life to a

Catholic rehab clinic. Her madame, Meg, rewards her big-money score with a fix,

then tells her about an arrangement with a real high-roller who’d asked for

Elizabeth personally. She meets the reptilian Keerson (played by Jean-Louis

Roux, actor, playwright, staunch anti-separatist senator and, according to

Wikipedia, “briefly the 26th Lieutenant Governor of Quebec, Canada” ) on his

private yacht, driven there by his personal driver. Keerson tells her to strip

and then demands that she tell him personal facts about herself, her life and

her background, leaving her more naked than she’s ever been.

Clues lead Henderson deeper into

previously-unknown territory. The metal container, he learns, is a “pyx”, a

lunette used by Catholic priests to transport a consecrated host to someone

sick, in-firm or otherwise unable to physically make it to receive communion.

Combined with the inverse crucifix, Henderson uncovers a Satanic cult, with

Elizabeth right in the middle of an important ritual—one that may or may not

have succeeded, depending on how Miss Lucy died.

This is a pyx.

Based on the novel by Canadian author, John Buell,

and directed by casual Star Trek director

Harvey Hart, The Pyx is primarily a

straightforward police procedural, naturalistic in the pattern of Serpico or The French Connection. The viewer is never an active participant in

the investigation, always held back as if by some line of invisible police

tape. We watch Henderson interact with his partner, Det. Paquette (Donald

Pilon); we see him violently interrogate a frustrated suspect, but we’re not

part of the mystery.

Conversely, we’re much more involved with

Elizabeth’s story, drawn into her life with intimate close-ups, put at a

distance only when Elizabeth closes off to the people around her—particularly

when dealing with Meg—or when she’s shooting up. In these moments in

particular, the direction is to make us feel like intruders.

The biggest problem with The Pyx as a film is with its structure. It isn’t readily apparent

that the parallel storylines are subsequent, that we’re witnessing Elizabeth in

a previous time, even though we’ve seen her lying dead beneath the opening

credits. There are no visual or even textual indicators that we’re in the past

when Elizabeth is on screen. When the body is identified as “Elizabeth Lucy”,

then we’re introduced to the woman alive, then told of another hooker who has

disappeared, at least I was duped into thinking that perhaps this was a matter

of mistaken identity. The missing hooker was mis-identified as Elizabeth, her

storyline was happening concurrently with Hendersons and at some point the two

would come together. There’s a definite disconnect once the realization of

time-shifting hits and it takes a while to get back onto track.

Whether or not this was intentional on the part of

the filmmakers is open to debate, of course. For my part, I had to stop after

Keerson’s interrogation of Elizabeth and restart the movie to see where or if

I’d missed something. It’s a definite misdirection and since the movie spent

many years in the public domain (I first found it as part of a multi-disk

horror collection), I started to wonder if this print was missing footage, or

if this was a different edit entirely. A quick glance at a second “official”

DVD told me otherwise; this was apparently the intended edit.

Strangely, the title character, the Pyx itself,

barely figures at all in the movie. Little attention is drawn to it in way of

close-ups; it is explained in almost off-hand dialogue (delivered by Pilon via

clumsy American dubbing), and its signature scene, featured so prominent in the

film’s trailers, is nothing more than a quick cutaway during the climax.

If the above weren’t enough to give one pause,

there’s also the matter of Karen Black’s inconsistent performance, which is

predominantly flat when she’s attempting to appear aloof and soul-dead. It’s

difficult to tell when she’s supposed to be smacked-out and when she’s just

shut off from Meg or another john. She only shines during her first scene with

Keerson, and it really is a powerful sequence which left me feeling as

emotional exposed as she was. On either side of this scene, however, it’s hard

to generate any sympathy or concern for Elizabeth. She’s just not that

interesting. (And speaking as one who could never get past Black’s wandering

eye, which I’ve always found distracting—my problem, not her’s—Black never

seems present in the film, as if she’s being directed by two conflicting points

of view, but not in service of the character.)

If the above weren’t enough to give one pause,

there’s also the matter of Karen Black’s inconsistent performance, which is

predominantly flat when she’s attempting to appear aloof and soul-dead. It’s

difficult to tell when she’s supposed to be smacked-out and when she’s just

shut off from Meg or another john. She only shines during her first scene with

Keerson, and it really is a powerful sequence which left me feeling as

emotional exposed as she was. On either side of this scene, however, it’s hard

to generate any sympathy or concern for Elizabeth. She’s just not that

interesting. (And speaking as one who could never get past Black’s wandering

eye, which I’ve always found distracting—my problem, not her’s—Black never

seems present in the film, as if she’s being directed by two conflicting points

of view, but not in service of the character.)  Christopher Plummer is Christopher Plummer. If you

liked him in everything else he’s ever been in, you’ll like him in this. As

Henderson he’s alternately determined or blandly appealing. The scenes were he

attempts to be a tough guy fall flat. Pilon, for what little he has to do, is

far more intimidating, possibly because his character is in service of the

story and, as a result, a cypher.

Christopher Plummer is Christopher Plummer. If you

liked him in everything else he’s ever been in, you’ll like him in this. As

Henderson he’s alternately determined or blandly appealing. The scenes were he

attempts to be a tough guy fall flat. Pilon, for what little he has to do, is

far more intimidating, possibly because his character is in service of the

story and, as a result, a cypher. As stated, there are multiple prints of The Pyx floating around, some under the

title The Hooker Cult Murders and in

various degrees of watchability. It’s actually pretty easy to luck out and land

a widescreen copy on one of the numerous portmanteau collections, but there are

also some dreadful full-screen copies as well, with no panning-and-scanning to

speak of, so beware of versions focusing on tables with knees at either side.

It’s an unusual movie and, at risk of being racist, a very Canadian thriller as

well: low-key and lacking urgency, but getting the job done in the end.