The story of Sir Gawain, the bravest knight of

Camelot, and his encounter as a squire with the mysterious Green Knight is one

of the best-known stories in Arthurian legend. While it appeared in various

forms, its definitive version comes from an unknown 14th Century

author (known among academics as the “Pearl Poet” due to North West Midland dialect

idiosyncracies in the stanzas, or more familiarly “The Gawain Poet”--J.R.R. Tolkien was a big fan and contributor to the poem's preservation), who wrote

a long-form poem depicting the young knight’s adventure.

Gawain, a brash and wide-eyed youth, was but a

squire in Arthur’s court on the New Year’s Feast when the Green Knight burst

through the hall’s doors and proposed a wager. Who among them would take the

Knight’s mighty axe, strike a single blow and behead him. The catch? “Should

the power remain in his body” he would deliver a blow in kind within a year and

a day. Bewildered and suspicious of the challenge, the other knights were

hesitant to take up the challenge, but young Gawain, seeing the others injuring

the King’s honor, accepted. But once he delivered the blow, instead of dying

the Knight simply picked up his head, waggled the bloody part at Queen

Guineviere, and told Gawain he would see him at the Green Chamber, the Knight’s

fortress, one year and a day from then.

Instead of mourning his last year, Gawain

decides to seize his remaining time. Rewarded by Arthur of a knighthood, Gawain

set off on grand adventures of chivalry, honor and chastity. At several points

during his wanderings, he finds himself tempted by seductive women,

particularly the wife of a lord who has given him shelter. He rebuffs her three

times and on the last night, she rewards his honor with a gift of a magical

green girdle (or shirt or sash, it varies) that will protect him from harm.

Hedging his bets, Gawain meets with the Green Knight on the appointed time.

However, he flinches before the Knight can deliver his killing blow. Laughing,

the Green Knight reveals himself to be the Lord who gave him shelter, that he

knows Gawain is cheating by wearing the girdle and instead gives the lad a mild

cut on the back of his neck, a reminder of his last-minute cowardice and a

lesson in gallantry to the end.

Ultimately, the whole ordeal is revealed to

have been a trick of Morgan Le Fay, the enchantress and Arthur’s sister, who

wanted to embaress the King and frighten Guineviere. Gawain was just a pawn and

yet emerged a hero despite his failings.

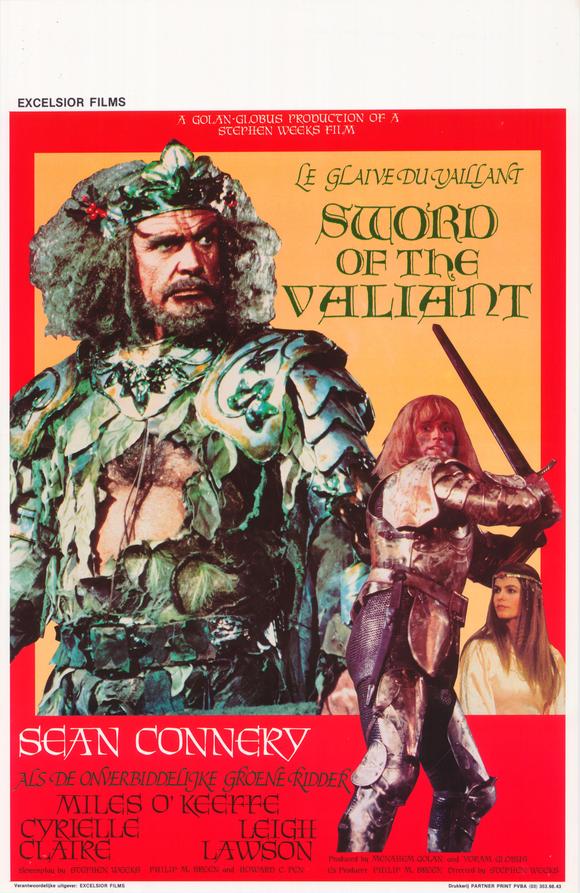

Sword of the Valiant is the cinematic retelling of

this classic tale.

Sorta.

A pet project of British director Stephen

Weeks, he’d already filmed the tale once before in 1973 with Murray Head as

Gawain, but a dispute between producers and studios hampered production and the

film was never given proper distribution. So when Yoram Globus and Menahem

Golan, the Israeli equivalents of Dino DeLaurentis, offered Weeks the

opportunity to redo the movie, Weeks leapt at the chance. He loaded his cast

with a handful of heavy lifters in British entertainment including Raiders

of the Lost Ark co-star John Rhys-Davies, Peter Cushing in a completely

sitting-down role as the Senechal, veteran character actor Trevor Howard as the

King, and for the coup de gras, superstar Sean Connery (who was filming Never

Say Never Again simultaneously) as the Green Knight. (He’d even managed to

bring back Rhys-Davies’ fellow Raiders allum Ronald Lacey to reprise his

role as the villainous Oswald from the previous incarnation of the film.) And

while he really wanted Mark Hamill to round out the cast as Gawain, Messers

Golan and Globus insisted on another international superstar to play the hero:

Miles O’Keeffe. After his impressive and acclaimed debut in Bo Derek’s Tarzan,

the Ape Man, not to mention all those stellar Ator movies, he was an

obvious slam-dunk to play the role of one of the greatest knights in mythology.

Following the success of John Boorman’s Excalibur,

Sword of the Valiant probably seemed great on paper. And it starts quite

well with Connery’s magnificent entrance astride a white horse, his horned

crown and armor glittering green, he looks magical. Good timing too, since “The

King” (the name “Arthur” is never uttered, nor are any of the be-bearded

knights), has just finished bitching that all his nobles have gone soft after

wretched peacetie has settled over the land. “The Old Year limps to its grave

ashamed,” he says, and demands to see some proof that knightliness exists

within his castle walls.

Bathed in emerald light, the Green Bond uses

his axe to cut through a helmet, proving its sharpness. “Let any of you take up

my axe and hack the head from my shoulders. One blow only. And if the power be

left in me, I demand the right to deliver a blow in the same manner.”

When no one steps up, the King is about to

accept but squire Gawain leaps to the rescue. He’s knighted on the spot and the

Green Knight laughs. “I ask for a knight but what do I get? A youth that has

not yet earned his beard.”

So Gawain beheads the Knight, a headless

Connery picks up the (lousy animatronic) head and reattachs it (both the

beheading and reheading are achieved by pretty fancy invisible cuts and whip

pans). The Knight grants Gawain his year and even grants him a loophole. Gawain

keeps his head as long as he can solve a riddle:

Where life is emptiness, gladness

Where life is darkness, fire

Where life is golden, sorrow

Where life is lost, wisdom

(Connery’s horse does not want to stand still

during this poem.) And he tells Gawain to seize his year, “Only fools and

priests squander life by fearing death.”

So off goes Gawain, his new squire, Humphrey (Leigh Lawson),

and his new armor—all of which once belonged to King Maybe-Not-Arthur and

leaves Too-Small-for-Camelot to “seek his beard”.

And oh! The adventures. Ten minutes from the

castle, he requires a church key to remove his codpiece and relieve himself.

And Humphrey just happens to have one. Then he decides to eat a unicorn, since,

being rare and magic, it’ll probably taste better. But that creature

disappears, a tent appears in its place and an Enchantress sends them to Lyonesse,

for no real particular reason.

Gawain defeats the “Guardian of Lyonesse”—a

land in which no man has entered nor cannot leave—leading to a circular logic

that comes from updating medieval texts for the mass market—but after taking

the wounded man back to the town, the dying Guardian points at Gawain and calls

him his murderer. He’s able to escape the angry mob because the beautiful

Linnet (French actress Cyrielle

Clair clumsily dubbed) gives him a magic ring that lets him disappear but

reveals him to the Eye of Sauron… no, wait, it just makes him disappear.

Anyway,

other things happen. He rescues Linnet, then loses her. Then the Green Knight

tells him using magic is cheating and not part of the game. So he gives it up,

meets two of the dwarves from Time Bandits (David Rappaport and Mike

Edmonds), they send him somewhere else, he rescues Linnet again and then loses

her again, this time to the lustful Lord Oswald and his Senechal father (who

wishes to use her to bargain with a rival lord, played by Rhys-Davies doing a

Brian Blessed impression).

Then more

stuff happens. A lot of walking left, then right, particularly in extremely

claustrophopic stone corridors and staircases, which could come from shooting

on location in real castles in Wales and France. He’s involved in numerous

uninspired fights, clunky sword duels and one of the worst-shot battle

sequences in recent memory (involving a cast of dozens!).

Along the

way, Gawain uncovers the mystery of the riddle save the last stanza, earns his

spurs (or beard, once he can grow one) and meets the Knight on the appropriate

day. Only this time, he’s wearing a sash of invincibility that Linnet gave him,

which allows him to cheat again, battle the Knight and finally learn how wisdom

is acquired through loss of life.

And

credits.

Though I

have not yet seen Weeks’ previous incarnation of the story, I’m told that Sir

Gawain and the Green Knight resembles Monty Python and the Holy Grail

in terms of production value. Sword of the Valiant also has much in

common with the quotable Pythonian-Arthurian take, but mostly accidentally.

Everyone in it seems to be having a good time, particularly Connery, but

O’Keeffe is slightly better in motion and silent than he is when having to

deliver lines like, to his torturer, “Does your mother know what you do for a

living?” Much of his delivery is stiff and sore-thumb contemporary. When he’s

not talking, he looks okay in a romance novel-cover type of way, even when he’s

trying not to fall over in his clunky armor (borrowed from Royal National

Theatre and the Old Vic). But even taking that aside—I mean, who goes “Miles

O’Keeffe! What a thespian!”—there are many moments where he cuts an impressive,

knightly figure.

Even the

clumsy action and photography can be forgiven, particularly with a modern eye,

as the staging and angles call to mind some of Robert Taylor’s bosoms-and-armor

pics like Knights of the Round Table or even Ivanhoe. They’re

costume dramas and at heart so is Sword of the Valiant. The lame

attempts to modernize the dialogue aside, it’s an earnest attempt at a story of

chivalry, even if most of the source material is jettisoned in favor of

Gawain’s and Linnet’s love story.

If you

drop all of the niggling faults, there’s an interesting allegory going on under

the surface that actually does call to mind the endless interpretations of the

original poem. Scholars over the years have called Gawain and the Green

Knight a Christ analogy, an early work of feminist literature (due to

Morgan Le Fay calling the shots and even in young Gawain’s passive nature),

even an early look at queer literature (though given the time it was written,

this has been determined to be quite a stretch), due to a subplot in which

Gawain must deliver a kiss to the Lord harboring him. The Green Knight is

usually interpreted as the Green Man of European folklore, the guardian of the

woods and an embodiment of nature. Sword of the Valiant takes this

course as well. While the climactic scene seems rushed (likely due to Connery’s

schedule on the non-Bond Bond movie), as the Green Knight dies from his wound,

his green fades to white and he starts to crumble like snow, leaving the idea

that The Green Knight was Gawain’s entire borrowed year. It’s an interesting

idea and it even allows for a rewatch (which does reveal little hints to this

end throughout), but by this point, you may done the first time through.

But, wait Mike,

if this movie isn’t all puppies and blowjobs, why bother seeking it out? Good

question, particularly due to the controversy surrounding the domestic DVD

release. For all its missteps, Sword of the Valiant was gorgeously shot

in 2.35:1 widescreen and makes wonderful use of the real locations (in some

scenes anyway). But since it did bupkis at the box office and is pretty much

reviled, the only way to get it is to locate the out of print DVD which, of

course, is in an ugly cable-adapted pan-and-scan version, leaving one to focus

solely on faces and acting. There is a silver lining for collectors with

multi-region players: a 2.35:1 DVD is available as a Polish import and

sometimes that version shows up on YouTube.

So to

answer my self-posed question: that’s my riddle for you. See you back here in a

year and a day.