“This is the story of the triumph of good over evil,” we are told by the opening titles. “Obviously it is a fantasy.”

It is said that Molière and La Fontaine used to frequent the Cafe de l'Alma in the Chaillot district of Paris. But today it is visted by a group of leaders, including The Chairman (Yul Brynner), The General (Paul Henreid), The Commissar (Oskar Homolka), and The Prospector (Donald Pleasence), who privately refers to them as, “Just faceless, ordinary monsters.” Together, they form the Board of Directors of International Substrate, and they have hatched a plan to dig up Paris in order to get to the oil that lies beneath the city.

Now, it is well known that all districts of Paris have their own dotty protectors, the Madwomen, if you will. The titular "Madwoman of Chaillot" is Countess Aurelia (Katharine Hepburn, in her best performance as far as I'm concerned), who prefers to live every day as one specific date. “First, the morning paper. Not these current sheets full of vulgar lies. I always read the Gaulois for March 22, 1919. It’s by far the best. Delightful scandal. Excellent fashion notes. And of course the last-minute bulletin on the death of Leonide Leblanc. She used to live next door. And when I learn of her death every morning it gives me quite a start. To recover from which, Chaillot calls. It is time to dress for my morning walk. That takes much longer without a maid . . .”

She’s not so mad as to imagine that life really is the same as that one March morning. Time is passing, of course, but it’s not like she has to acknowledge it. “Of course, in the morning it doesn’t always feel so gay. Not when you’re taking your hair out of the dresser and your teeth out of the glass. And particularly if you’ve been dreaming that you’re a little girl on a pony looking for strawberries in the woods. But then comes a letter in the morning mail. One you wrote to yourself, giving your schedule for the day. Then, when I have washed in rosewater and put on my pins, rings, brooches, pearls, necklaces, I’m ready to begin again.”

The Prospector’s son, a radical activist named Rodrick (Richard Chamberlain), brings the Board’s scheme to the attention of the genteel lady, as well as her cadre of peers, including the waitress Irma (Nanette Newman), the Folksinger (Gordon Heath) and her most confident of confidants, the Ragpicker (Danny Kaye). “The world is being taken over by the pimps,” says master Ragpicker.

The Countess is appalled, “The world is unhappy? Why wasn’t I told?”

So distraught is she by this news of scheming, of men living life as if it was disposable, Countess Aurelia gathers the other Madwomen of the districts—Josephine, the Madwoman of La Concorde (Edith Evans), Constance, the Madwoman of Passy (Margaret Leighton), (Josephine, the Madwoman of La Concorde (Edith Evans), and Gabrielle, the Madwoman of Sulpice (Giulietta Masina). Together with the street people, her people, she desides to hold a trial for these despoilers, in absentia. The rich men and their destructive ways are represented by The Ragpicker.

“Criminals are always represented by their opposites,” assured Josephine, who was to be the judge. The trial was absolutely necessary, for something had to be done.

“If you kill them, they’ll be missed,” protested Constance. “And we’ll be fined. They fine you for every little thing, you know?”

To which the Countess replies, “Do you miss a cold when it’s gone? They’ll never be missed.”

Thus, the Ragpicker prepares the case, defending against the charge that he and his ilk worship money.

“Worship money? Me?” says the Ragpicker. “I plead not guilty! I don’t worship money. It’s the other way around. Money worships me. It won’t let me alone. The first time money came to me, I was a mere boy. Untouched. Untainted. It came quite suddenly when I innocently picked a bar of gold bullion out of a garbage can while playing. As you can imagine, I was horrified. I tried swapping it for a little, rundown one-track railroad. To my childish amazement this immediately sold itself for a hundred times its value. I made desperate efforts to get rid of this unwanted wealth. I bought refineries, department stores, every munitions factory I could lay hands on. The rest is history. They stuck to me. They multiplied. And now I am powerless. Everyone knows the poor have no one but themselves to blame for their poverty. But how is it the fault of the rich if they’re rich? Oh, I don’t ask for your pity. All I ask for is a little human understanding.”

He continues, “Ah, without money nobody likes or trusts you. But to have money is to be virtuous, beautiful, honest and witty. To have none is to be ugly and boring and stupid and useless.”

“One last question,” asks the Countess. “Suppose you find this oil you’re looking for? What will you do with it?”

“I’ll make war! I’ll destroy what remains of the world!”

When the trial concludes the verdict is clear: guilty. But how to carry out the sentence, and what shall the sentence be?

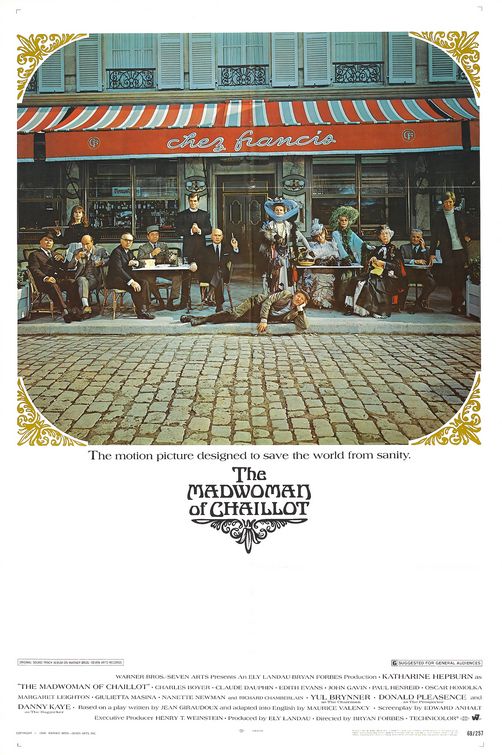

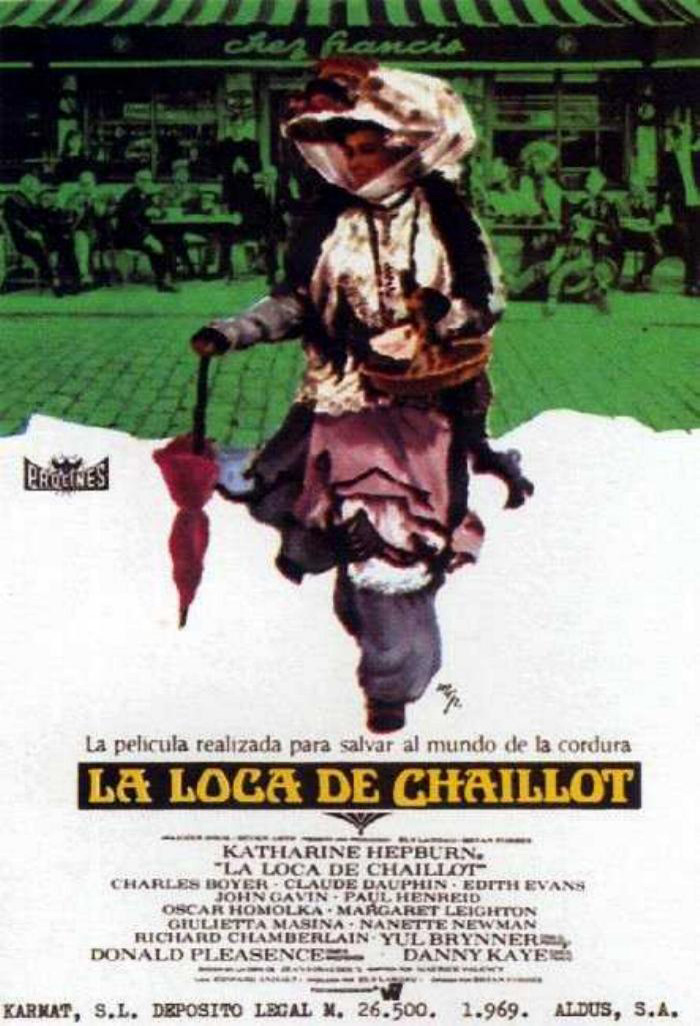

The Madwoman of Challot began life as the play, La Folle de Chaillot, written by acclaimed writer Jean Giraudoux and was first performed in Paris in 1945, a year after his death. In 1949, fellow playwright Maurice Valency adapted the story into English and it was warmly received in the United States. Subsequently, the play was reworked by Inherit the Wind authors Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee (with music and lyrics by Jerry Herman) into the musical Dear World, which won star Angela Lansbury a Tony Award. That same year, 1969, screenwriter, producer and pulp writer (with wife Edith), Edward Anhalt (The Boston Strangler), adapted the Valency script for the big screen, which was directed by Bryan Forbes (Séance on a Wet Afternoon). The film premiered in October, was met with favorable reviews from critics and not-too-shabby attendence, then quietly bowed out of the limelight, fading away with the final breaths of the “Summer (and Autumn) of Love”.

Anhalt’s screenplay adheres closely to Giraudoux’s play and embellishes only where he needs to. Just the same, spending the first act with the odious Board members gets a little tedious. While it is indeed fun to watch Brynner rail against the indignities he must suffer every day when exposed to the world’s rabble, the sequence becomes a slog. After about ten minutes, you’ll catch yourself saying, “I get it. They’re evil, cruel capitalists. What else is new?” But if you can stick with the movie until Hepburn’s marvelous Countess is introduced, the movie becomes a delightful ride from there. Until it slows down again with the introduction of the other Madwomen. Their first scene together unfortunately drags as well, mirroring the Board’s callousness with their own fractured-mirror outlooks on life. But the reward for coming this far is without question Danny Kaye’s moment as the Ragpicker during the trial. Assuming the collective persona of all cruel overseers and misers, the Ragpicker seems to shock himself by the end with the imperious self-righteousness he finds within. It’s a chilling moment of black comedy and the centerpiece of the film (as, I’m sure, it was the centerpiece of the play) and Kaye left me breathless, at least.

The particulars of The Madwoman of Chaillot are, unfortunately, timeless. The rich will always run roughshod over the poor and life is wasted on the forward-thinkers, only appreciated by the young and the mad. And while the underlying themes are also universal, this particular movie seems more appropriate today than it might have in the post-war Paris of the ‘40s or mid-war America of the late ‘60s. The Madwomen and the street people, including the idealistic Irma and Roderick, could easily fit the mold of the modern “Occupy” movement; the Board of Directors are an easy surrogate for Wall Street and Corporate Culture. As the opening title card points out, almost bitterly, the results are pure fantasy.

While Anhalt invented scenes involving The Prospector and his son inside their home (where Pleasance’s character collects and displays old bathroom doors, hanging them on the wall as modern art), they wisely resisted the temptation to update the play for modern times. The Café and the Countess’s domiciles exist in stasis, the first eternally quaint and the latter decaying along with its owner’s mental stability, yet still retaining its dignity. Certainly Roderick and the Board members are given a more modern cut of suit, no hippies or swinging Londoners lurk in the background of the frame. The story stays put in its fantasy time period and could be easily trotted out for any generation.

Unfortunately, it really could be applied to any generation, as class warfare is less cyclical than it is a never-ending hypno-spiral. But how lovely would it be if we could just round up our ruthless rulers, bankers, despoilers and pimps and just march them off the end of the Earth? It’s of course an insurmountable solution. The best we can do is get up, dress up in our best, and pick a personal time from our past where life was perfect, without the simple evil of reality shattering our illusions of happiness.

For therein lies the true tragedy of The Madwoman of Challot: in the end, the Countess’s world has been intruded. Tomorrow may again be March 22, 1919, but it won’t change the fact that yesterday was quite gloomy, cold and hard.

Again, we must bow our head in silent prayer to the Warner Brothers Archives for preserving this handsome oil painting brought to life (thanks to the photography of Burnett Guffey and Claude Renoir). At the moment, it’s available as one of their movie-only standalone DVD-Rs, but it’s better than nothing at all. Amazon also has made it available on their Instant Video Service.

For another take on the story, be sure to check out the novelization on Richard Chamberlain’s website.