In a perfect world, all critics would approach every piece

of art with an open mind, judging it only against itself in terms of success or

failure. But since critics are human beings, and our knowledge is based on past

experiences, that approach will never happen, so we have to rely on

intellectual filters to avoid bias. If, as a critic, one can attain

self-awareness and avoid self-righteousness, then your reviews will reflect

fact and opinion honestly.

Obviously, this isn’t just the failing of critics. Everyone

dislikes at least one movie for not being what they expected. I’m just as

guilty as anyone. I did not review Cronenberg’s History of Violence when

it was released, not because it departed so radically from the graphic novel it

adapted, but because it went in a third direction I didn’t anticipate. I wasn’t

expecting David Cronenberg, of all artists, to take the storyline into familiar

action movie territory. Because the movie didn’t live up to my ill-conceived

expectations, I felt resentful towards it for some time. (Maybe I should be

proud of myself for not expressing those feelings in print, instead of the

more-reasonable reaction of being disgusted with myself for setting my own

trap.)

Fortunately, I knew going into it that I was going to be

biased, both pro and con, towards Killer Joe. First, I was already

pre-disposed to liking it because of director William Friedkin’s first

adaptation of a grim Tracy Letts’ play, Bug. Bug was my intro to Letts’

surreal Southern Gothic gallows humor and Killer Joe is the only of his

plays I’ve seen performed live. It’s a violent, crass and grotesquely funny

slice-of-horror involving a white trash family and a hired killer. People are

violently assaulted and bloodily murdered on stage throughout the course of the

film (effects in this case courtesy of A Far Cry From Home’s Benzy).

There’s also a better-than-fair amount of nudity in the play, made much more

graphic by my position in the front row, about a foot or so from the stage.

Plus, these were local actors who I knew for the most part and, considering the

play opens with the lead actress bare from the waist-down, again, a little over

a foot from my face, it’s hard not to get involved. The second act opens with

the titular character, a corrupt Dallas police detective, completely nude, feet

from my face, and during which time seemed to slow down to eternity (again,

small theater).

[From the Pittsburgh City Paper:

in background, from left) John Gresh,

Lissa Brennan, John Steffanauer

and Hayley Nielsen, and (foreground)

Patrick Jordan in

barebones productions' Killer Joe. Photo by Ilya Goldin.]

I was blown away by Letts’ script, shocked by the violence

(I dodged a flying chicken leg during the climax), and astounded by several of

the performances. In particular, I was struck by Haley Nielsen, who played the

family’s possibly brain damaged pseudo-Lolita, Dottie. Dottie sleepwalks and

sleeptalks, says odd things at inopportune times and appears almost psychic at

others. She’s damaged and fragile and is the audience’s anchor to the

story—even if you couldn’t care about the other characters, doomed and damned

by their own bad decisions, you want to see that Dottie is safe in the end.

Nielsen, a local actress I wasn’t familiar and thus wasn’t saddled with any of

my personal baggage, performed Dottie with a far-away, almost ethereal quality,

fully aware of what was happening, yet at the same time far-removed and

emotionally stunted. Dottie is the key character in Killer Joe, all of

the action revolves around her to some degree, and I think any performance of

the play would hinge on the actress playing her. So, as a fan of the play, I was simulataneously excited and

trepidatious about a film adaptation. Given Friedkin as a director, I figured

the story was in good hands, particularly with Letts adapting his own script

for screen. Because Billy F. never struck me as a guy who particularly gave a

shit about mainstream success, I figured all the violence and sex would remain

intact. My biggest fear, though, was not who would play Joe but Dottie.

Friedkin could stick Adam Sandler in the title role and still pull off a good

movie. But Dottie… no Hollywood actress even came to mind.

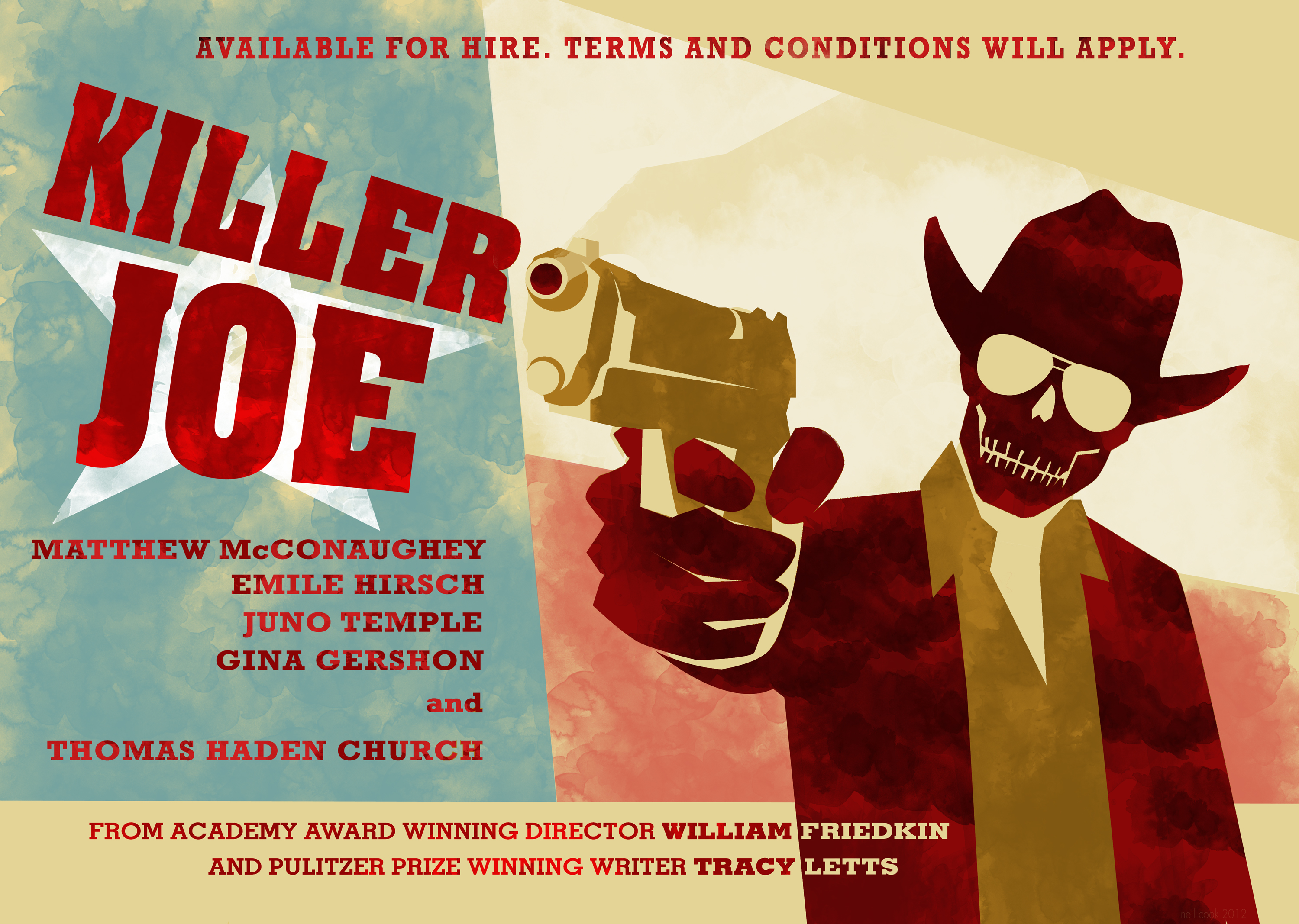

[Image found at http://www.spectacularoptical.ca]

Just like the play, Killer Joe begins with Chris (Emile

Hirsch) banging on his father’s trailer door, begging to be let in. He is

answered by his stepmother, Sharla (Gina Gershon)—she’s naked from the

waist-down and her crotch is in his direct line-of-sight. This is how both

Letts and Friedkin establish the sophistication of the crowd. “You answer the

door like that?” Chris demands.

To which Sharla replies, “Shut up—I didn’t know it was

you!”

“Class” is not an issue with these people. So it comes as

no surprise that Chris is in debt to drug dealers and wants to hire someone to

kill his birth mother for $50K worth of insurance money. It’s less of a

surprise when his wet-brain father, Ansel (Thomas Hayden Church), less than a

generation older than his son, puts up little argument against the plan.

Somebody told Chris “about a guy” who does murder-for-hire, Dallas cop Joe

Campbell (Matthew McConaughey), aka “Killer Joe”, and Chris figures that the

guy might be charitable enough to do the job on spec and take a cut of the

insurance money after. But Joe isn’t the kind of guy to give away murder

services and demands twenty-five grand up front, non-negotiable. The story

might have ended there, with the Smith family returning to their no-class

hovel, if it weren’t for Dottie (Juno Temple). As a baby, Dottie’s mother tried

to suffocate her with a pillow because “she was young and didn’t want to give

up her life.” It didn’t work, obviously—Dottie just “wasn’t” for a short

while—and returned to the land of the living as a constant disappointment. When

Joe asks Dottie how she knows this happened, being an infant and all, Dottie

replies, “I remember it.”

Dottie is part of the family without serving any specific

function. Ansel treats her like a little girl; to Chris, she’s the only shred

of anything good; to Sharla, she’s just around, to make dinner or run errands.

Emotionally, Dottie is twelve and no one does anything to help her mature. The

only giveaway that she’s older is her body and her unconsciously-hyper

sexuality, which disturbs Chris’ dreams and enchants Joe. Joe agrees to do the

job as long as Dottie is his “retainer”.

Joe and Dottie’s “first date” starts off uncomfortable

enough. She rebels at wearing a cocktail dress and is sobbing when Joe arrives.

He speaks kindly to her, but matter-of-factly, without condescension, without

walking on egg shells around her. Midway through their meal, he puts an end to

her incessant absent-minded and skittish babbling by having her stand up,

remove her clothes and put on the dress for him. As in the play, this is an

electrically creepy moment but for completely different reasons. On stage,

Nielsen stripped in front of Joe and, thus, in front of the entire audience,

rendering herself completely vulnerable and not just to him, but to the

audience. It’s meant to draw forth instinctual protectiveness from everyone

watching, accentuating that Joe is a predator. But in the film, Friedkin stages

the action in a single shot where Joe stands with his back to Dottie as she

changes. The camera doesn’t focus on her nudity but it doesn’t shy from it

either. What we focus on, then, is a similar transition in Joe’s character, but

one with far more menace. Never once does he face her, and barely looks at her

even when he moves her in front of him, and instead keeps his eyes on some

faraway spot on the ceiling. “How old are you right now?” he asks.

“Twelve.”

“So am I.”

By now if you’re expecting any kind of happy ending, I wish

I could live a day inside your mind.

The underlying violence begins to ripple forth at this

point, as Joe installs himself in the family’s trailer and their life. Chris’s

sense of morality keeps butting up with his instinct for survival and he

continually flip-flops over the plan—kill her, Joe; don’t kill her, Joe—and

then he focusses purely on rescuing Dottie, who at this point may not even need

to be rescued. But since Chris hasn’t made a single winning move since the film

started, the outcome, to quote the Magic 8 Ball, “is doubtful”.

Friedkin plays Letts for all its worth, squeezing every

drop of amorality and depravity onto the screen. Even if you know all the beats

of the story, the violent beats are still shocks of cold water. And everyone in

the film holds their own. Matthew McConaughy is a stand-out as the cold-blooded

Joe, who is sweapt out to sea by the dotty Dottie. There is a moment, after

Sharla has been beaten and humiliated, where the camera stays in tight close-up

on Gina Gershon’s face and you know she’s never been better. Emile Hirsch as

Chris and Thomas Hayden Church as Ansel keep our sympathies in the air like a

heated game of volleyball. None of the Smiths are remotely bright; their

desperation drives their mundane existences and there’s no real loyalty lost

between them. It’s almost too easy for a reptile like Joe to slide in and

dominate them all, especially when they think they can use chest-beating to

gain the upper hand.

So it all comes down to Juno Temple as Dottie. Not an

illogical choice, given her impressive performance in Atonement. (Hey,

it got her into four collective minutes of The Dark Knight Rises.) In Killer

Joe, she is uninhibited and unashamed, her vulnerability is communicated by

her big doe eyes and post-pubescent movements. And it’s here that my objective

dissonance took hold. It’s entirely unfair to compare Temple’s performance to

an actress in a regional production of the play, but Hayley Nielsen was my

introduction to the story and her performance defined the character to me. As

Dottie, Nielsen was ephemeral and on another plane of existence than the rest

of the characters. Most of her lines were delivered in a breathless and excited

monotone, every line a declaration and, thus, a non-sequiter. For me—and only

for me, obviously—Temple was too grounded in her portrayal of Dottie. Within

tight close-ups her Dottie was never farther from me than Nielsen,

spacially-speaking, and her fragile, damaged persona is in perfect service of

the story and script. But she had a physical presence that Nielsen

intentionally abandoned, and it drags the rest of the story, and all of its

horror and grit and despair, down into the gutter where it began. Temple Dottie

struck me as too real. The rest of the family you could meet at any Wal-Mart in

the country. A physical realization of Dottie, even though she is a “pure”

character, brings these low-lifes into too-sharp of a relief.

But a real Dottie allows for a more

believable Killer Joe. I have no real proof in my suspicion, but I think it

would be an easy temptation for actors to play Joe as a bad-ass, smooth and

over-the-top thug who is only in control because he’s slightly smarter than

those around him. Everyone in the story is in danger of characature, just a few

millimeters off in either direction will result in something balloony and lumpy

from a Ralph Bakshi movie. But McConnaughy plays Joe as a well-oiled

psychopathic watch, a mass of coiled springs contained by the exterior. His

interaction with Dottie brings out a different man, a man used to control but

unused to an unpredictable factor like Dottie. Though he does manage to possess

her, there’s something of her at work on him beyond her childish sexuality. She

mentions “pure love” several times throughout the film, and what Joe feels for

her is obviously far from pure, but maybe to his mind it is. His interest in

her may be a result of something human unlocked inside of him. As with Dottie’s

nudity, Joe’s interaction with her allows for something vulnerable to shine

out. It isn’t redemption, but it isn’t the revulsion you’re meant to feel

during a live performance.

It could be quibbling, but this leads to one point of

genuine disappointment in the film. In the play, Joe’s dominance and subjugation

of the family is presented at the beginning of the second act. Having been

brutally beaten by the drug dealers, Chris collapses through the trailer’s

front door. Instead of Sharla, he encounters a completely naked and

gun-weilding Joe. Thinking Chris might be a burglar, Joe has lept out Dottie’s

bed and onto Chris as the complete alpha male. On stage, it’s shocking,

naturally, and awkwardly funny and uncomfortable, but it establishes Joe’s new

position in the dynamic. Like Beowulf, he’ll face his greatest challenges with

only a weapon and the skin he was born in.

In the film, Friedkin declines to show McConaughey in his

full-frontal glory. It’s obvious that he’s completely nude, but the reveal

isn’t as strong. We stay on a neutral point of view as Chris crashes through

the door and Joe is already waiting for him on the other side. Visually, it

removes a great deal of dynamism from both the scene and Joe’s character. In

the film, instead of a Grecian athlete or an unbridled predator, he’s simply a

naked guy with a gun. An argument can be made for many things—that it cheapens

Temple’s and Gershon’s nudity, that it was staged thusly to avoid further

problems with censors (even though Friedkin allowed the film to go to theaters

unrated, which waters down this latter argument). All it does is diminishes the

ferocity of the scene. I’ve thought it over and come to the conclusion that

this is a thematic mistake. My issues with Juno Temple’s performance are my own

hang-up.

With all the other fearless choices made with the material

it’s disappointing that Friedkin and/or McConaughey--to quote an actor I’ve

worked with who is accustomed to nude scenes--“pussied out on the dick shot”.

Ultimately, a play isn’t a movie and a movie isn’t a play

and critics should remember that before they waste time writing a review.

Report on the art you saw, not the art you expected. And definitely don’t watch

Killer Joe without a designated moral compass.

[Special blame goes to Eric Thornett (writer/director of A Sweet and Vicious Beauty) for originally dragging us to the play in 2009.

Seen this movie a month ago and to say the truth, this movie is very problematic and i'm not sure what opinion i truly have on him.

ReplyDelete