In 2008, Roger Ebert wrote a piece for his

SunTimes blog titled, “This is the dawning of the Age of Credulity”, in which

he relates a conversation he had with Taxi Driver author Paul Schrader. “He told me that after Pulp Fiction, we

were leaving an existential age and entering an age of irony. ‘The existential

dilemma,’ he said, ‘is, 'should I live?' And the ironic answer is, 'does it

matter?' Everything in the ironic world has quotation marks around it. You

don't actually kill somebody; you 'kill' them. It doesn't really matter if you

put the baby in front of the runaway car because it's only a 'baby' and it's

only a 'car'.’ In other words, the scene isn't about the baby. The scene is

about scenes about babies.”

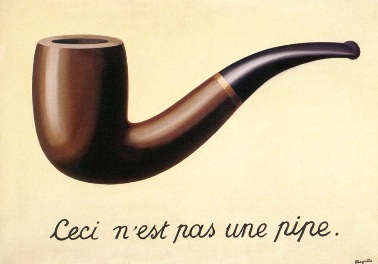

Which I feel was more than adequately boiled

down by Rene Magritte in his painting, The Treachery of Images (La

trahison des images, 1928–29), a painting of a pipe which he captions,

"Ceci n'est pas une pipe": “This is not a pipe.” And it isn’t. It’s a

painting of a pipe. “The famous pipe,” Magritte lamented. “How people

reproached me for it! And yet, could you stuff my pipe? No, it's just a representation,

is it not? So if I had written on my picture "This is a pipe," I'd

have been lying!” (Torczyner, Harry. Magritte: Ideas and Images. p. 71.)

Taking this all further, Ebert noted about the

cinematic culture around him, “We may be leaving an age of irony and entering

an age of credulity. In a time of shortened attention spans and instant

gratification, trained by web surfing and movies with an average shot length of

seconds, we absorb rather than contemplate. We want to gobble all the food on

the plate, instead of considering each bite. We accept rather than select.”

Taking this all further, Ebert noted about the

cinematic culture around him, “We may be leaving an age of irony and entering

an age of credulity. In a time of shortened attention spans and instant

gratification, trained by web surfing and movies with an average shot length of

seconds, we absorb rather than contemplate. We want to gobble all the food on

the plate, instead of considering each bite. We accept rather than select.”Modern movies, from this point of view, are

neither self-contained nor created in a vaccuum. Every movie is made of

particles from other movies. “Homage” has moved beyond the in-joke, background

detail or set-piece and into literal and thematic presentation. So much of this

is personified by Quentin Tarantino and his contemporaries. They’re not making

movies, they’re making their versions of movies that had come before. “I told

Robert [Rodriguez], ‘You made your Fistful of Dollars with El

Mariachi, now’s the time to make your epic, your Once Upon a Time in the

West”, sez the world’s most successful fanboy on the audio commentary for Once

Upon a Time in Mexico. It’s like the self-referential humor of The

Family Guy: “That’s funny because I get it.” The Inglorious Basterds was

neither a remake of The Inglorious Bastards nor simply a World War II

adventure, but it was Tarantino’s WWII movie. Coming up is Tarantino’s

spaghetti western, Django Unchained.

For better or worse, we’re slowly coming out

of the age of irony and/or credulity because the most recent crop of

movie-goers, including but not limited to the Twi-hards, are simply unaware of

what came before, so every movie cliché is new to them. I remember a Twilight

fan swooning over Edward because, “When he says cheesy stuff, it’s sincere

because he doesn’t know it’s cheesy!” And thus we get Total Recall for

this generation, Red Dawn for this generation. And this generation

doesn’t know that they’re cheesy retreads, thus, they’re sincere.

All of this is a backhanded way of introducing

Ward Roberts new film, Dust Up, because it lands somewhere between

ironic and post-ironic. Produced through his Drexel Box production house, Dust

Up at first glance is a loving send-up of ‘70s exploitation, the

“grindhouse” genre that is all the rage. Ironic because it takes the

market-driven selling points of gratuitous sex, violence and mayhem and

embraces them. Post-Ironic because it takes the most ludicrous of these

elements to their logical conclusion. And post-credulous because it does it

with sincerity, honesty and a passion for all of the sources that came before

it. And in the end, Dust Up is not “Ward Roberts’ exploitation movie”; Dust

Up is Ward Roberts’ Dust Up. It takes all the other-movie particles

and molds them into something from his point of view and his sensibilities, and

those of his collaborators, and makes something that’s both familiar and

outrageous at the same time, but never seems derivative. It’s a balancing act

to be sure, and on either side of the tightrope lies disaster. Fortunately,

Roberts and company manage the middle walk very well.

Dust Up is about

the accidental—if not destined—collision of five people. New mom Ella and her

junkie husband Herman, and two opposing forces: the stoic and enigmatic

peaceful warrior Jack (Aaron Gaffney) and his Indian sidekick Mo (Devin Barry) on

one end; the twisted and gleefully evil narcissistic personality Buzz on the

other. Jack wears an eyepatch, a constant reminder of a tortured past as a

violent soldier; Mo wears a Jay Silverheels outfit and yellow-striped tube

socks, to both honor and mock his Native American forebears who have gotten

rich and fat off of casino living. Buzz (Jeremiah Birkett) ingests chemicals,

tortures people and declares everything to be his: “This is MY house. The House

of Buzz. In the Land of Buzz. In the Time of Buzz.”

Ella (Amber Benson) is a young mother living

in a house with severe plumbing problems. Her husband Herman (fellow filmmaker

Travis Betz), a roadie for Hoobastank (of all things), went a little loopy

after the birth of their daughter, Lucy, and is now holed up at Buzz’s in a

drug-induced, debt-heavy sabattacal. In need of clean water, Ella picks Jack’s

name out of the phone book—the way of this peaceful warrior is that of the

handyman. This is before Ella learns of her deadbeat spouse’s debt to

psychopath, Buzz. Actually, Buzz is much more than a psychopath, more than a

sociopath. He’s a charismatic, amoral, self-affirming bar owner-cum-cult leader

who promises those he doesn’t like—or happens to notice—with death via

dismantling at the hands of his chief thug, Mr. Lizard. What’s more amoral than

a sociopath? An anthropath, perhaps? Whatever, you don’t want to owe

money to Buzz.

You know what annoys Buzz more than being owed

money? Owing money to someone else. In this case, the corrupt, racist Sherriff

Haggler (The Hills Have Eyes remake’s Ezra Buzzington), who wants his

payoff and demands it in a most demeaning fashion. The laws of physics dictate

that shit rolls downhill, to Buzz calls in poor Herman’s marker, gives him 24

hours to get the money and then has Mr. Lizard eject him from the bar in a most

unfriendly fashion.

Over the course of a few scenes, Jack becomes

involved in Herman’s plight because it has become Ella’s plight. Jack is cut

from the same cloth as most wayward heroes on the path of

redemption—particularly Shane, according to an interview with Roberts at the Daily Grindhouse—so he isn’t likely to leave a damsel in distress. Before

you jump to conclusions, he’s doing this out of pure spirit. Yes, Herman is a

junkie, a bad husband, irresponsible, lazy, most likely unwashed and very much

an ungrateful jerk, but these facts aren’t lost on anybody. The deeper he drags

Jack (and Mo) into his pit of karmic despair, the more everyone—even

Buzz!—questions why they’re bothering to help him out at all. The lesson to be

taken away is if you’re going to be a selfish schlep of a person, you’d better

have a pretty and capable wife and an adorable baby at home. Otherwise even

Mother Theresa would be inclined to throw you to the wolves.

As can be expected, things spiral out of

control, epically and apocalyptically. Jack attempts to make good on Herman’s

debt by lending him half of the money he owes Buzz in a show of good faith, but

Buzz isn’t one to focus on problem-solving. In a matter of minutes, the casual

morning meeting results in Buzz accidentally blowing up his bar—it’s a Rube

Goldberg-esque chain of cause and effect, but the end result is that Buzz

accidentally shoots one of his meth chemists mid-cook and, as we all know, meth

is a most volatile and tempermental chemical potion. Emotionally, it’s the

fourteen-year-old-girl of drugs.

The rest of the film could be titled “Buzz’s

Bad Day”, as he punishes everyone in his path for his own misfortune. He and

reason aren’t even in the same time zone, and if you’re wondering if depravity

has a baseline, as far as Buzz goes, the answer is ‘no’. He does know how to

whip up a freak frenzy. Unfortunately, he doesn’t choose his followers wisely.

Drug-addled desert-scum aren’t known for their stamina, no matter how many

barbecued human bodies they’re fed. This is best demonstrated when Buzz

declares, “It’s orgy time!” and receives the same dismayed reaction as if he’d

announced a pop quiz.

Dust Up was

obviously crafted to be a fun time for all, and it’s one of the rare movies,

indie or otherwise, that is as much fun to watch as apparently it was to make.

Behind it all are smart filmmakers who know which conventions to turn on their

heads and which ones to embrace. As wacky as Dust Up is it never once

tries to act like it’s better than either the genre or its audience. Unlike

recent “grindhouse” movies like Hobo with a Shotgun, Dust Up wasn’t

designed as a party tray of excess and nihilism. It asks you to care about its

characters and then gives you characters to care about. Every one of the actors

is pitch-perfect in their performances so it’s hard to single any one out.

Gaffney’s a terrific hero archetype, violently opposed to violence lik Billy

Jack, but with the smooth vocal tones of Joel McCrea. Barry brings just enough

dry wit to Mo to comment on the insanity of things—even his own actions—without

becoming hipster about it all. As Herman, Travis Betz—whose amazing allegorical

demon cabaret, Lo (starring Birkett as the title character), introduced me to the majority of the versatile

cast—gives the jerk of a catalyst an affability that earns a little bit of

redemption at the end. Birkett doesn’t so much steal every scene he’s in as he

attempts to corner the market on it. Buzz could all too easily be a cartoon

villain, the word “Evil” given bushy eyebrows and pop eyeballs, but Birkett

hints at a humanity buried deep beneath the viciousness and drug-induced

paranoia. Both he and Jack project a loneliness and sense of loss, making them

each other’s dark mirror. Perhaps the hardest job was placed on Benson’s

shoulders. The filmmaker/author has the dubious honor of portraying the lone

sane person in this sea of multi-colored insanity. Like Bob Newhart in all

incarnations, she’s the only rational one in the room at any given time, and

she does it with a sense of humor that anchors all the madness together.

Roberts, Betz and Benson not only love film

but understand it as well, as they’ve proven through this movie and previous

offerings like Betz’s Joshua and Benson’s Drones (which she

co-wrote and directed with Adam Busch). They’re not into the popular mash-ups

of movie iconography and theme so much as they are into creating new forms from

previously-used clay. As far as Dust Up goes, Roberts has taken the

history of movies he loves and built upon it, rather than attempt to reflect it

in some mirror he fractured himself. The result is both familiar to those who

know the territory and unique at the same time. A ‘70s sex ‘n death-fest with

an altruistic attitude taken from Howard Hawks westerns. A salute to what came

before even as it moves forward.

As the saying goes, “This is Dust Up.

There are others like it, but this one is…” Roberts’, Drexel Box’s, and now

ours.

No comments :

Post a Comment